Why investors are heading back to Ukraine - WSJ

John Mazarakis got rich lending money to cannabis companies and running a chain of pizzerias along the Eastern Seaboard. His next big bet: houses and industrial parks in war-torn Ukraine.

Mazarakis and the $2 billion asset manager he co-founded, Chicago Atlantic, are preparing to invest as much as $250 million in the country. He isn’t alone. Steel-nerved investors are trickling back into Ukraine, lured by the chance to help the country in its fight against Russia—and to score assets on the cheap.

“We come from out-of-favor industries, which makes it easier for us to fund a $10 million deal in Ukraine tomorrow,” Mazarakis said. “The country could use the help now, and we have the bandwidth to do it.”

Prospects for Ukraine’s economy remain fragile. Republicans in Washington, who control the House, have become increasingly skeptical of supporting Ukraine.

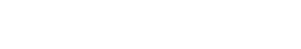

Losing long-term backing from its biggest financial supporter would derail a nascent economic rebound in the country. Activity expanded in the second quarter for the first time since the start of the war, after a devastating 29% contraction in 2022. Businesses and households have adapted to life during war, buying diesel generators to get through blackouts and moving to cities in western Ukraine.

“U.S. support is significant and is decisive,” said Andriy Pyshnyy, Ukraine’s central-bank governor. “If we lose regular financial assistance from the United States, this will undermine the very basis of this stability.”

That doesn’t scare investors like Mazarakis. He made his first trip to Ukraine in September, flying first to Kraków, Poland, and then crossing the border on foot. His team was picked up by a security detail, which drove them down a narrow highway to Kyiv.

His firm plans to form partnerships with or give loans to Ukrainian developers to build affordable houses and apartments. Chicago Atlantic also plans to invest in longer-term industrial projects. He projects they will earn returns of about 20%.

John Mazarakis, in dark jacket, and Chicago Atlantic, the asset manager he co-founded, are preparing to form partnerships to support Ukrainian development. PHOTO: CHICAGO ATLANTIC

“This is binary. If Ukraine loses the war, obviously we lose everything,” Mazarakis said. “If Ukraine wins the war, we will be able to deliver the return we’re quoting or much higher.”

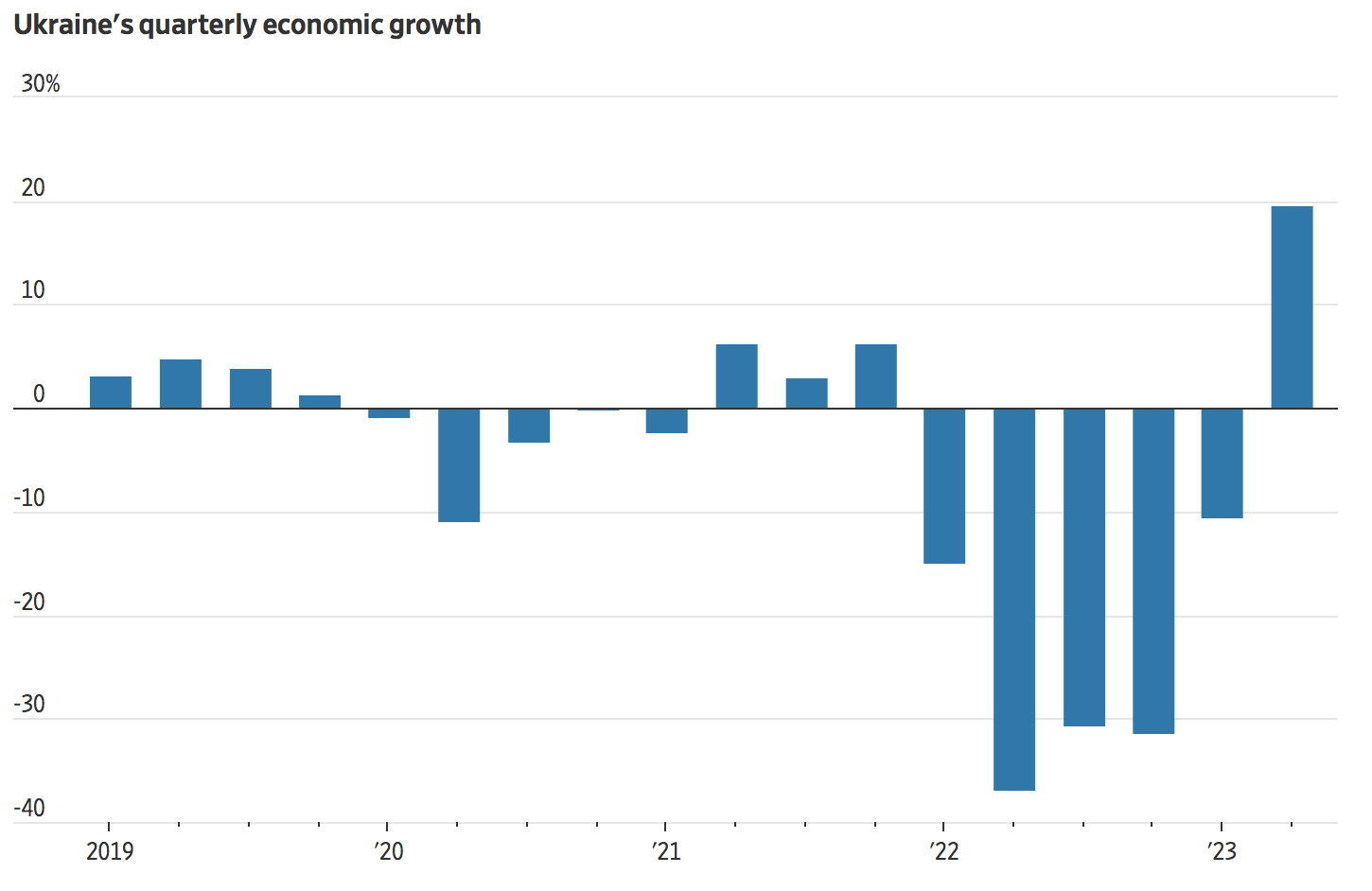

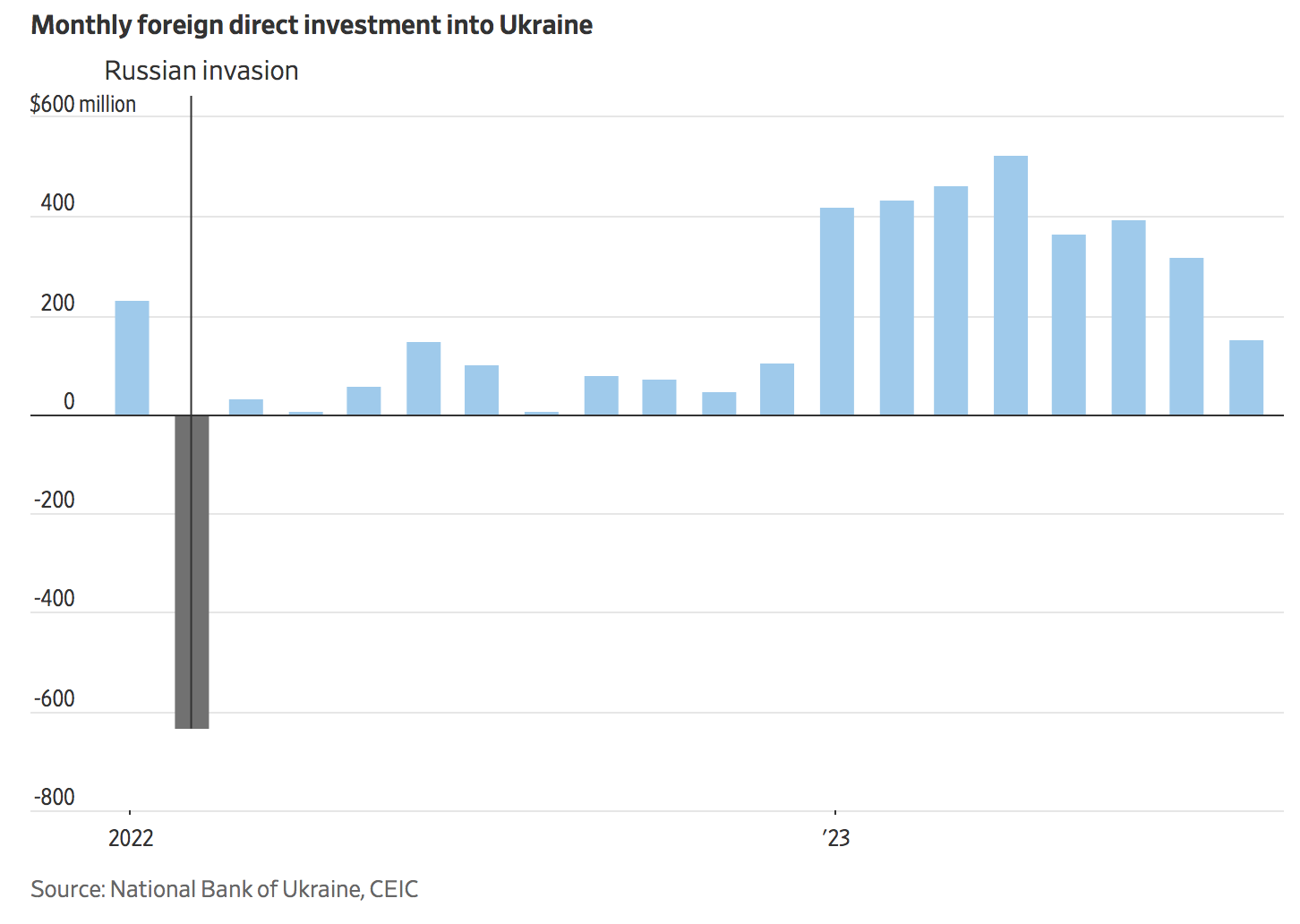

Ukraine received $3.1 billion in foreign direct investment this year as of August, including reinvested earnings, after a slight contraction in the same period last year. Prices for many overseas government bonds have jumped roughly 50% since May, though they continue to trade at a deep discount.

Germany’s Bayer recently broke ground on a $60 million-plus expansion of its seed factory west of Kyiv, and Nestlé is expanding its instant-noodle factory in the west of the country.

Among the projects that Ukraine has been seeking funding for: $27 million to build a tomato-processing plant in Mykolaiv, $118 million for a brick factory near Kyiv and $6 million for a honey-processing facility in the Dnipropetrovsk region.

“We have way more requests, have more investment projects than we had even before the war,” said Sergiy Tsivkach, who leads the Ukrainian government’s investment-promotion office.

A slowdown in inflation, as well as a record $40 billion stash of foreign currency, has allowed the central bank to start cutting interest rates and loosen its grip on the currency, the hryvnia.

The longer-term process of rebuilding Ukraine will be enormous. Areas that have been liberated from Russian control are already confronting those obstacles, as businesses struggle with labor shortages, land mines and limited access to loans from Ukrainian banks.

President Volodymyr Zelensky has estimated that reconstruction will cost more than $1 trillion. Many mainstream investors remain hesitant to put money in an active war zone. Ukraine is high up in global corruption rankings, often appearing alongside countries such as Iran and Sierra Leone.

Investing in Ukraine comes with unique challenges. Bomb shelters are mandatory for new construction projects. Hiring a security detail and sport-utility vehicles can cost $10,000 a day. Many health- and life-insurance policies won’t cover war zones. Additional insurance coverage is $1,500 a day or more.

A major private-equity fund in Ukraine tried to hold an investor conference earlier this year, but only a handful of foreign investors were able to secure insurance coverage. The event was later moved to Moldova.

David Iben, chief investment officer of Tampa, Fla.-based Kopernik Global Investors, is one of the largest foreign investors in two public Ukrainian companies: the agriculture company

Astarta

and the chicken producer MHP. He bought more of their shares after the war broke out.

So far, his bets haven’t paid off. Even before the war, his investments were under pressure from corruption, currency instability and corporate-governance problems.

“We’ll buy these things if we can get them at 10% of what they’re worth,” Iben said. “These are good companies that sell products that people need.”

Tomas Fiala, a Czech financier who leads the Ukrainian investment bank Dragon Capital, plans to invest $20 million this year. That is just a fraction of prewar levels, but enough to begin work on a new factory and complete the first stage of an industrial park outside Lviv.

“People are looking…but until the war is over, there will be little competition,” Fiala said.

Investors such as Dragon benefit from support from government-financed development banks including the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which agreed to invest almost $25 million in the Lviv project.

Dragon in September became one of the first investors in Ukraine to secure coverage against war-related damage, through the World Bank’s investment-guarantee arm. Its policy will cover almost $10 million in investment in the Lviv industrial park.

War insurance is seen as a critical step for facilitating investment in Ukraine.

Marsh McLennan recently launched a database it developed with the Ukrainian government that tracks damage done by Russian attacks. It shows that 66% of the country hasn’t suffered physical damage from the war, according to Crispin Ellison, who has led that effort for Marsh McLennan. The goal is to make it easier for private insurers and investors to assess risks of war damage.

“You’ll start to see high-risk investors starting to move into low-risk investments,” Ellison said, such as solar and wind projects.

Ukraine was expected to become one of the most popular destinations for foreign investment after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. It has fertile land, an educated population and is located ideally at the intersection of Eastern and Western Europe. Integrating Western capitalism and Soviet communism proved tricky.

“We spent a lot of time as lawyers not just negotiating but educating. I remember telling somebody that loans are supposed to be paid back,” said Peter Teluk, a Ukrainian-American lawyer who spent decades working as a lawyer in Kyiv. “They looked at me with surprise.”

Corruption, political volatility and a powerful oligarchy put off foreign investors. In recent years, Ukraine has undertaken changes, including an overhaul of the government’s anticorruption efforts and revisions to parts of its judiciary.

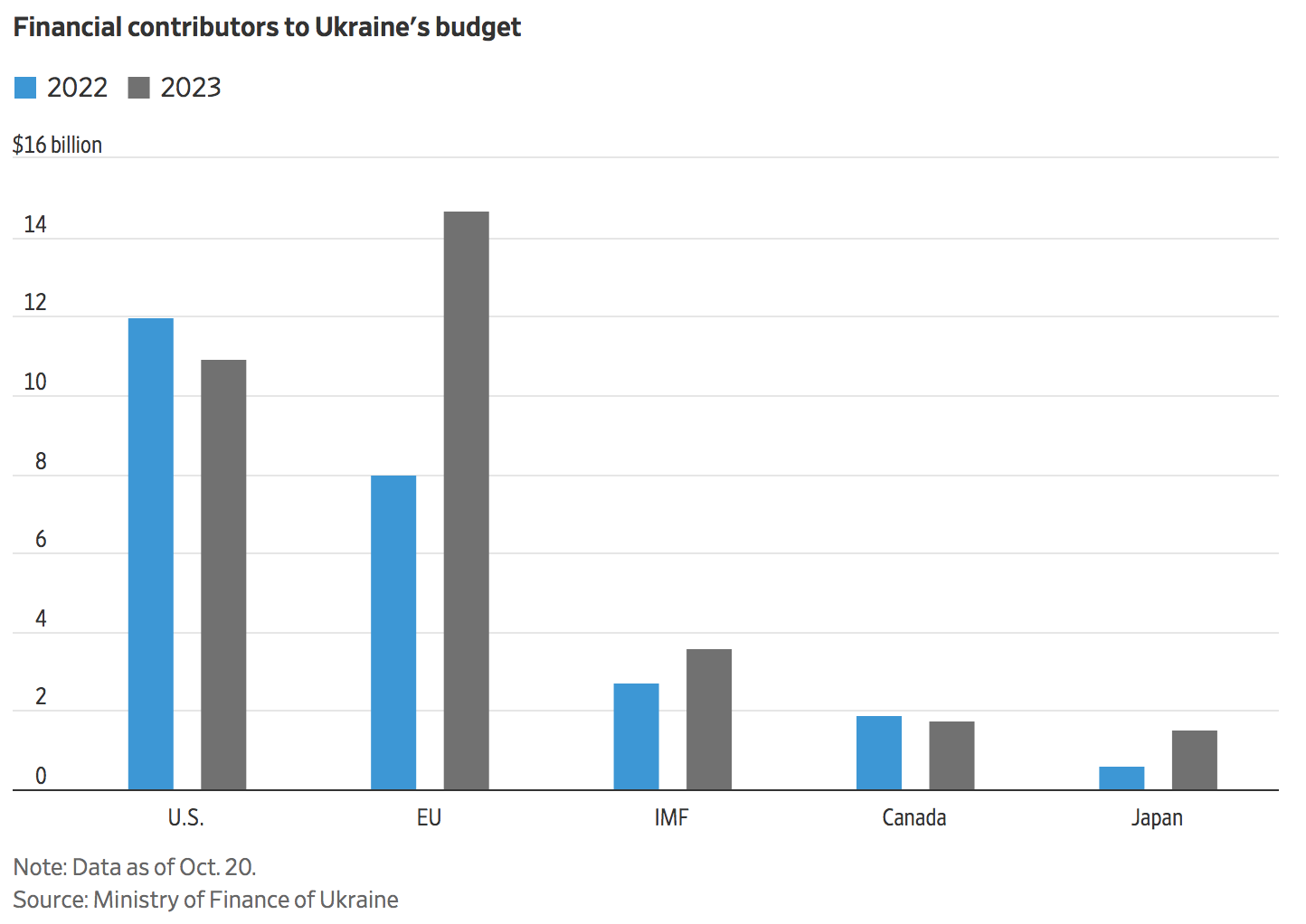

Pyshnyy said the country is committed to further changes required to gain European Union membership. But he warned it might end up backsliding on an economic overhaul if U.S. funding—Ukraine’s biggest source of financial support since the war began—is halted.

At risk are the National Bank of Ukraine’s shift to a more-flexible exchange rate and the end to central-bank money printing to fund the government. The loss of either initiative could deter foreign investors.

“All these achievements can be undermined if we return to monetary financing of the budget deficit,” Pyshnyy said. “It’s a budget of the war, with a lot of funds necessary for defense and the very survival of Ukraine. We must finance it under any conditions.”

Andrew Duehren contributed to this article.